The fourth part of the “dharma pracar workers” series deals with full-time acaryas (teachers): monks and nuns who dedicate themselves exclusively to Baba’s mission, renouncing their personal, social and family lives.

In order to become a WT (wholetimer), one must first spend time working as a LFT and then enter into training with an average duration of three years (with variations for more or for less), at the end of which the participants are already qualified to teach the philosophy of Ananda Marga. Then they go through one month’s training to learn how to teach the six lessons of sahaja yoga (the meditation system that margiis learn). At the conclusion of this stage, they are considered acaryas – people who teach by example.

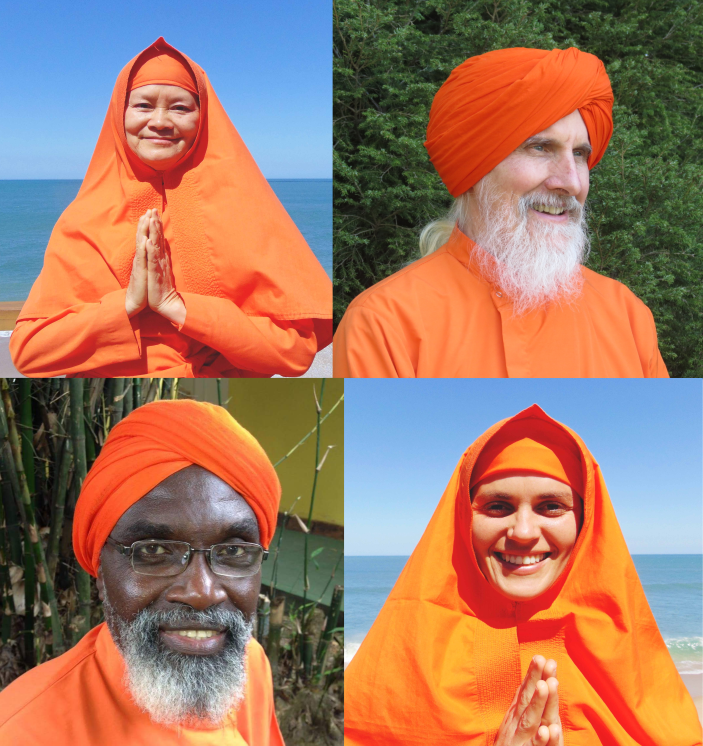

Each acarya then receives a “posting” – a place to work, which should be a far country from its place of origin. Exceptions to this practice exist. The new acaryas are initially called brahmacarii/ brahmacarinii (men/ women) and are dressed in white skirts and orange on top. After a few years of dedication, they receive a special lesson (kapalika) and begin to wear the entirely orange uniform. From then on, they are called avadhuta/ avadhutika (men/ women) and make a commitment: to work for the mission and for the ideology of Ananda Marga, for as many lives as necessary, until the last being becomes enlightened.

The story of Avadutika Ananda Sushiila Acarya, who currently works in Porto Alegre, RS (Brazil), represents well the path needed to become a WT. She began her journey serving for eight months as LFT in Taiwan (her native country). Then she spent a year and four months in the didi’s training center in the Philippines. Then she set out for acarya training in India. Gratuated in Economics, she had never thought of being a didi before, but the experience with Baba changed her mind to the point of feeling that nothing else attracted her.

“I had many doubts. Can I do it? Then, in a meditation I asked Baba: ‘You decide whether I’m going to be a didi or not, I can not decide.’ Baba did not answer me. So I told Baba: ‘If you make a specific gesture in your speech [to cross your two fingers] it means that I should become a didi. After three days I had a darshan with Baba in Bengali and I did not know what He was talking about. When it was over, Baba suddenly made a first gesture that I had thought of, but I thought with my mind, “Baba, this is not it.” Then Baba made the second gesture twice. Then he left and I felt the shiver. So this was the last sign so I had no more questions. That’s why I became a didi.”

Didi Sushilla said to be very inspired by her current moment, with several achievements. Among them, a Yoga Festival (http://festivaldeyoga.com.br/) and a series of workshops about the feminine. Didi, however, has already had difficult times, such as not having a home to stay. But resilience to difficulties is a characteristic that many didis and dadas claim to have, feeling there is something that keeps them in the mission. This is also what happened to Acarya Nirvedananda Avadhuta, who was born in Cameroon and now works in Brazil. He recently went through many health challenges – his biggest clash as a monk, he says. A pneumonia left him hospitalized in the ICU, followed by very strong spine pains that prevented him from sleeping and meditating. Instead of giving up, he feels that the challenges have further entrenched him in Baba’s mission.

Dada tells us that when he returned from the hospital, he had to be carried up, since he could not climb up the stairs from where he lives. Two days later, it would be the day to do kapalika meditation. He kept his promise, even needing help getting out of the house. The practice was so strong that at his return home he was able to climb the stairs alone. “Our ideal life is a challenge and the daily energy of kapalika develops devotion,” he says.

Until he met Ananda Marga, Dada thought that meditation was a religion – he was even becoming an atheist. However, he began attending dharmacakras regularly, having been initiated by a monk he had met in a lecture. Along with this, he received some asanas to practice. “When I started practicing yoga I felt God and I thought I could dedicate my life to teach it to people.” Dada planned his way very well, finished his studies of Economics and worked for a while in a stable public job. “The inspiration came slowly, it was built. In 1982, I decided that I would be a monk, but only left the country in 1987, with conscience.”

The Brazilian Brahmacarinii Shivanii Acarya awakened to spirituality very early, which led her to a great search. She experienced Hare Krshnas and Taoists, until she met Ananda Marga philosophy in a lecture by Acarya Jinanananda Avadhuta in Mato Grosso (Brazil). In 2013, she left her position as an art teacher at the state school and went to Paraguay to perform LFT training with Avadhutika Ananda Girishuta Acarya. When she finished, she returned to Brazil to work full time with pracar, organizing retreats, dharmacakras and inspiring girls to learn meditation, along with Avadhutika Ananda Jaya Acarya, who guided her at the time. These projects eventually made more sense than their former activities. At the end of 2015, she went to acarya training, which lasted 1 year and 10 months. She describes the whole process as “very beautiful and gentle,” and rejoices to have worn her acarya uniform for the first time at the important International Dharma Maha Sammelan event in Kathmandu, Nepal, in November 2017.

Nowadays, Didi Shivanii is in the south of Brazil, doing exactly what she thought was necessary in the country at first. Considering the demand of women in having the presence of a didi in their lives, she is happy to be able to initiate so many people. Working in the home country is exceptional, waiting for her visa to Australia. “Pracar changed my life, brought me a new horizon, opened the door for my spirituality to be alive, brought me hope for a better world. It was an invitation to become a didi.”

The story of Acarya Mahesvarananda Avadhuta begins in the United States at his age of 21, at a time when only hippies and weird people were doing yoga (he says he was a bit of both). With yoga, he began to feel energetic and, three years later, he was flying to India for monk training. He has worked for 14 years in Asia, 3 years in Europe and 22 years in South America. He explains that living in a different country with a different language, customs, food and behaviorism from his home country is a way of experiencing culture shock. And this shock, in his opinion, is a way to build world peace.

“People from these countries taught me a lot about hospitality, generosity, kindness, humility, community and helping each other. I believe that we can end hunger, poverty and war, and I have dedicated all my physical, mental and spiritual strength in this life, as I will in my future lives, to achieve this goal as soon as possible. I believe that together with His Grace nothing is impossible – we can change the world.”

Dada Mahesvarananda taught yoga and meditation in almost a hundred prisons and jails, in addition to having written some books. The two most recent are After Capitalism, Prout’s Vision for a New World, with the contribuition from Noam Chomsky, and Cooperative Games for a Cooperative World: Facilitating Trust, Communication, and Spiritual Connection: Facilitating Trust, Communication and Spiritual Connection. “I’m 65 now and I feel completely fulfilled. I would not trade this orange uniform for anything in the world. “

From Editorial Staff